Let’s just reiterate our starting position here: This happens at all stages of the life-cycle of a presentation, but if your base preparation is below par, then no amount of shiny graphics and animation will save you – sucky foundation, sucky presentation. To rise above the background noise of a zillion average-to-bad presentations, here are a handful of key questions to ask yourself as you put your thoughts together:

Do I really need to present? What do I want to occur as a result? What is the mindset of my audience? How am I going to structure my points? Do I need to use visual aids?

There are other questions of course, but these are the cornerstones.

- Do I really need to Present? Is gathering these people in a room and talking to them, with or without visual aids, the best way of imparting this information to this group of people? When I lecture on this topic, I facetiously suggest using anything from Pony Express to Skywriting to get your message across – precisely because as McLuhan said, in many cases the medium is the message. Would you be better off with six people sitting around a coffee table discussing some hefty tome of a report? How about a massive brainstorming session with 200 people with Post-it notes and lots of gophers. Maybe get your whole team down on a beach and the person with the conch shell gets to speak. Take your pick, but if your audience thinks you’ve got nothing of relevance to say, or that this is yet another ego trip by a manager with a PowerPoint fetish, no tool is going to help you.

- What do I want to occur as a result? If there is no call to action, there probably shouldn’t be a presentation. Even if your talk is purely informative, what do you want your audience to do with that knowledge? People need interpretation, not narration, and that is why you are up there. Tell them the data, tell them what you think it means and then get a discussion going on what you should all do about that. The starting point here is to define what constitutes a good outcome. If you’re a fairytale princess, it’s all about a castle and a handsome prince on a big white horse and everyone living happily ever after. In real life, it’s rarely that defined. Does the horse actually need to be white? At a pinch, would a truck do? Do you really need to be happy ever after, or just to end of this financial reporting period? Get clear. Really clear. What do you want them to do after your presentation? If you have no strong answer to that question, then you need to revisit question 1 again.

- What is the Mindset of my Audience? This is the big one, because it is only if you can catch a glimpse into your audience’s mind, that you have the possibility of changing that mind. Who are these people? Why have you been asked to talk to them? What, as a group, is their disposition? What about key individuals within that group? Are some of them more dominant or influential than others? What are their beliefs? Are they right or wrong? Are they open to hearing that they don’t possess all the facts? Do you have hard evidence to present to them or just strong opinions – and which are they more likely to respond to? Say you are making two presentations on the same day about equality issues and sexual harassment in the workplace. Your first audience is a bunch of late middle-aged, white, suit-wearing, male executives. You discover from your research that half of them belong to the same golf club – and that club does not admit women as full members. Your second audience are the founders and senior execs of a Web 2.0 company. Average age is late 20s, a third of the audience are women and the place has a reputation for being a meritocracy. Do you deliver the same presentation, with the same content, case studies and tone? What would happen if you tried?

- How am I Going to Structure my Points? Try telling a child a bedtime story without a beginning-middle-end structure and see how far you get. You will be interrupted every five seconds. “Who is this princess?” “What spell?” There’s a wolf? where did he come from?” “Why would a stepmother do that?” From the earliest age, we learn to take information on board sequentially. The poet Philip Larkin once said that bad storytelling is “beginning, muddle, end” and so it is for far too many presentations. What do you want your audience to do after you sit down? What is your point? How many elements do you need to break it down into in order to ram that message home? This is rarely a question of what you know, it’s a question of what do they need to know as a result of listening to you? That requires multiple drafts. One of the hardest things to do in compiling a presentation is to let your data go … You: “So there you have it. 66% of respondents preferred XX and that means 1 and 2 and 3.” Audience: “So what? You had me at 66%” OR “So what? 2 and 3 haven’t been relevant in this sector for over five years now!” Identify your audience’s trigger-points and build the anchors of your presentation around those. Place them in the order that is most compelling to that audience. Provide context at the beginning as necessary. And when you think you are finished drafting, distill it just a little more …

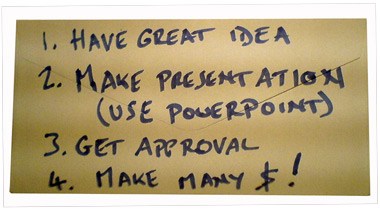

- Do I Need to Use Visual Aids? To PowerPoint or not to PowerPoint – that is another important question. Either way, I have found that the best way to start putting your presentation together is to stay away from your computer – and in particular from your presentation software. Talk to yourself in your car as if you were addressing this audience. Jot ideas down, or Dictaphone them as they occur to you. Capture little nuggets and phrases and thoughts. When you have the bones of your talk collated, lay out your story on paper. Then you can decide if imagery, or charts, or tables, will facilitate your audience’s comprehension, acceptance and retention of this information. If your ideas require graphs to explain them, or to prove their validity, then yes, you may need Slideware to put them across. But if your audience consists of lay-people, you may be better simply vocalising the result: “We ran a series of tests on this and in each case the XX was preferred by two-thirds of the audience when compared to the YY.” Do we really need to see 14 charts which do nothing more than reiterate that sentence over and over? Frequently presenters use Slideware because they lack confidence at some basic level – their slides are used as a roadmap, a shield or an AutoCue. If you are the expert, and you have credibility, then your audience will accept that 66% of people prefer XX over YY; you don’t need to sledgehammer the point home with your 14 colourful charts. Presenters who do this are usually missing the point. Okay, the data tell us that 66% of people prefer XX. So what? What do you want me to do with that information? That should be the focus of your talk, not getting mired down in p-values and confidence levels. That’s what handouts are for: “I’ve briefly summarised the data for you this morning, and you can find the age and socio-economic breakdown of the respondents in the handout. What we need to talk about now are the implications of these findings for our manufacturing facility.” If all you want to put on your slides are words, then it’s really time to stop and think. PowerPoint is not an AutoCue, no matter how many presenters you have seen using it that way. Nor should it be a crutch-like roadmap for you as a presenter; you either know your stuff or you don’t. So let’s assume you do know your stuff, would you be better off just talking to this audience? Because if your slides are all words, I would ask do you need to meet them at all (question 1 again!) or could you simply email them your thoughts in a Word document? Look at Ken Robinson on TED – no slides, no barriers, between him and the audience; just a beautifully thought out, beautifully expressed talk. Compelling. Memorable. Effective. Affective. Focus on your purpose, your message and your audience and you won’t go far wrong. Once you are clear on those, the details of tools and delivery will become apparent. Part 1 of this series is here. Next – Shaping your presentation